The letter to Vera Zasulich

Is there a non-capitalist road to socialism?

Introduction

Too much can be made of letters. In fact, too much is made of letters. A source that was not written expressly for publication is generally suspect as a statement of the author’s fully developed intentions or meaning. There are exceptions, of course, as when the author of a private letter expressly intends providing just such an authoritative statement. But even that has its problems, and never more so than when the author specifically declines to make certain aspects of their views public, yet we treat their unpublished words as canonical anyway.

Marx and Engels were prolific letter-writers. The 50-volume Marx-Engels Collected Works (MECW) concludes with 13 volumes, each hundreds of pages long, consisting of nothing but their correspondence. And, notwithstanding the preceding caveat, many stand out for their contribution to Marxism as a whole. The century and more of debate on base and superstructure, for example, is grounded in a handful of Engels’ letters.

One especially important letter – this time from Marx – was to Vera Zasulich. Zasulich was a prominent Russian Marxist in exile in Geneva. On 16 February 1881, she wrote to Marx, then residing in London, asking him to solve an important historical and political problem. What followed was perhaps Marx’s most sustained and best known attempt to explain how socialism might arise in a non-capitalist context. The result was ambiguous yet, given the perennial resistance to capitalism all around the globe, the topic of this brief correspondence remains important to this day. So the letter to Vera Zasulich continues to be widely cited.

However, the crucial element of this correspondence is not so much Marx’s explicit reply to Vera Zasulich and her comrades, which is quite bland, as the drafts of his eventual answer. Taken at face value, these drafts push Marxism in directions that are important for our understanding not only of nineteenth-century Russia but also of non-capitalist societies generally. So the question becomes, should the drafts be taken at face value – that is, as expressions of Marx’s fully developed position? This has been widely assumed by Marxists. Yet the letter Marx actually sent back to Vera Zasulich contains almost none of the details found in the drafts, so what does this omission mean?

More importantly still, if they cannot be taken as canonical, and we should approach the drafts to the letter to Vera Zasulich far more warily than in the past, does this leave open any route to socialism other than via capitalism?

1. The letter from Vera Zasulich

On February 16 1881, Vera Zasulich despatched a brief letter[1] to Karl Marx. She presented Marx with a dilemma that is still widely felt by Marxists, especially outside the great hubs of mature industrial capital.

Marx had long predicted that socialism would emerge more or less directly from the womb – or the grave – of capitalism. For capitalism would not only develop society to the point where socialism was feasible but it would also create the conditions in which capitalism itself was no longer economically sustainable and a socialist revolution was politically possible. But Zasulich’s concern was with what was still a decidedly non-capitalist society: Russia. True, there were small pockets of bourgeoisie and a smattering of workers and even revolutionary socialists in the cities. However, their influence over society was small. Mostly Russia was dominated (in terms of population and economic system) by a huge peasantry and (in terms of political power over the economic base as a whole) by an aristocracy with little interest in social development, at least in any direction that would favour socialism. From a Marxist point of view, the dominant forces and relations of production were wholly unsuited to a socialist revolution at any foreseeable time, but capital itself would plainly not be ripe for a long, long time. So what were socialist revolutionaries living in non-capitalist societies supposed to make of Marx’s work? Was there any hope?

In Zasulich’s own words:

For there are only two possibilities. Either the rural commune, freed of exorbitant tax demands, payment to the nobility and arbitrary administration, is capable of developing in a socialist direction, that is, gradually organising its production and distribution on a collectivist basis. In that case, the revolutionary socialist must devote all his strength to the liberation and development of the commune.

If, however, the commune is destined to perish, all that remains for the socialist, as such, is more or less ill-founded calculations as to how many decades it will take for the Russian peasant’s land to pass into the hands of the bourgeoisie, and how many centuries it will take for capitalism in Russia to reach something like the level of development already attained in Western Europe. Their task will then be to conduct propaganda solely among the urban workers, while these workers will be continually drowned in the peasant mass which, following the dissolution of the commune, will be thrown on to the streets of the large towns in search of a wage.

If one read only Marx’s writings on capitalism, one possible answer would be straightforward:

Nowadays, we often hear it said that the rural commune is an archaic form condemned to perish by history, scientific socialism and, in short, everything above debate.

But this is by no means an entirely compelling position:

‘But how do you derive that from Capital?’ others object. ‘He does not discuss the agrarian question, and says nothing about Russia.’

Hence the writer’s request:

So you will understand, Citizen, how interested we are in Your opinion. You would be doing us a very great favour if you were to set forth Your ideas on the possible fate of our rural commune, and on the theory that it is historically necessary for every country in the world to pass through all the phases of capitalist production.

2. Marx’s existing view of Russia[2]

At the time he received Zasulich’s letter, Marx had already spent years studying Russian and Russia,[3] and had already stated his overall position regarding the development of socialism in Russia via a non-capitalist route.

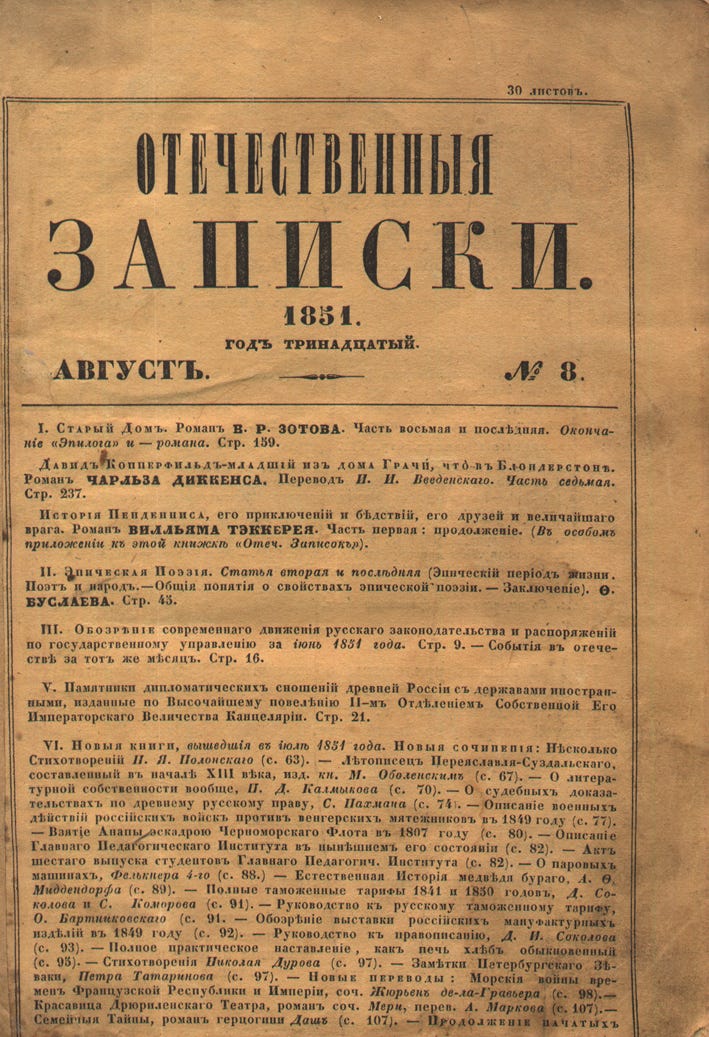

Writing to the editorial board of Otecestvenniye Zapisky in November 1877, he summarised the Russian situation as he then saw it:

If Russia wants to become a capitalist nation after the example of the West-European countries – and during the last few years she has been taking a lot of trouble in this direction – she will not succeed without having first transformed a good part of her peasants into proletarians; and then, once taken to the whirlpool of the capitalist economy, she will have to endure its inexorable laws like other profane peoples.[4]

But this tendency was not, in Marx’s view, inevitable, and persisting with it would, at least from a socialist point of view, be an immense error:

If Russia continues to pursue the path she has followed since 1861, she will lose the finest chance ever offered by history to a people and undergo all the fatal vicissitudes of the capitalist regime.

Marx denied that the model of historical development set out in Capital could be generalised into –

an historico-philosophic theory of the general path of development prescribed by fate to all nations, whatever the historic circumstances in which they find themselves.

For this interpretation would ignore the fact that –

events strikingly analogous but taking place in different historic surroundings led to totally different results. By studying each of these forms of evolution separately and then comparing them one can easily find the clue to this phenomenon, but one will never arrive there by using as one’s master-key a general historico-philosophical theory, the supreme virtue of which consists in being supra-historical.

In short, the lessons of capital and capitalism are many but they are not universal.

3. The drafts[5]

But just what are the lessons Marx had learned through his researches, and by whom can they be adopted? The gist of the drafts is easily stated:

1. The analysis presented in Capital relates solely to more or less developed capitalist societies, and is not appropriate to other modes of production. As Marx himself puts it:

I thus expressly limited the ‘historical inevitability’ of this process to the countries of Western Europe.

2. What is more, the central process with which Marx is concerned is not the development of capitalism as such. Rather:

In the final analysis, it is a question of the transformation of one form of private property into another form of private property…

Thus the expropriation of the agricultural producers in the West served to ‘transform the private and parcelled property of the labourers’ into the private and concentrated property of the capitalists. But none the less it is the substitution of one form of private property for another form of private property. In Russia, on the contrary, it would be a question of substituting capitalist property for communist property.

3. The peasant commune therefore offered a novel, entirely non-capitalist potential for social development.

In Russia, thanks to a unique combination of circumstances, the rural commune, still established on a nationwide scale, may gradually detach itself from its primitive features and develop directly as an element of collective production on a nationwide scale. It is precisely thanks to its contemporaneity with capitalist production that it may appropriate the latter’s positive acquisitions without experiencing all its frightful misfortunes…

Disregarding all the miseries which are at present overwhelming the Russian ‘rural commune’, and considering only its constitutive form and its historical surroundings, it is first of all evident that one of its fundamental characteristics, communal ownership of the land, forms the natural basis of collective production and appropriation. What is more, the Russian peasant's familiarity with the contract of artel would ease the transition from parcel labour to collective labour, which he already practises to a certain extent in the undivided grasslands, in land drainage and other undertakings of general interest.

4. In fact the full development of the commune after the emancipation of Russia’s serfs in 1861 was only prevented by the diversion of immense social resources to other purposes. Had they been directed towards the communes, things would have been very different.

If at the time of emancipation the rural communes had first been placed in conditions of normal prosperity; if the immense public debt, mostly paid for at the expense of the peasants, with the other enormous sums provided through the agency of the State (and still at the expense of the peasants) to the ‘new pillars of society’, transformed into capitalists, – if all this expenditure had been applied to further developing the rural commune, no one would today be envisaging the ‘historical inevitability’ of the destruction of the commune: everyone would recognise in it the element of regeneration of Russian society and an element of superiority over the countries still enslaved by the capitalist regime…

From the time of the so-called emancipation of the peasants the Russian commune has been placed by the State in abnormal economic conditions and ever since then it has never ceased to overwhelm it with the social forces concentrated in its hands. Exhausted by its fiscal exactions, the commune became an inert thing, easily exploited by trade, landed property and usury…

This combination of destructive influences, unless smashed by a powerful reaction, is bound to lead to the death of the rural commune.

5. This oppression by the state exacerbated existing conflicts within the commune.

This oppression from without unleashed in the heart of the commune itself the conflict of interests already present, and rapidly developed the seeds of decay. But that is not all. At the expense of the peasants the State has forced, as in a hothouse, some branches of the Western capitalist system which, without developing the productive forces of agriculture in any way, are most calculated to facilitate and precipitate the theft of its fruits by unproductive middlemen. It has thus cooperated in the enrichment of a new capitalist vermin, sucking the already impoverished blood of the ‘rural commune’.

6. Endogenous developments also threaten the commune.

Apart from all the malign influences from without, the commune carries the elements of corruption in its own bosom. Private landed property has already slipped into it in the guise of a house with its rural courtyard, which can be turned into a stronghold from which to launch the assault on the communal land. That is nothing new. But the vital thing is parcel labour as a source of private appropriation. It gives way to the accumulation of personal chattels, for example cattle, money and sometimes even slaves or serfs. This movable property, beyond the control of the commune, subject to individual exchanges in which guile and accident have their chance, will weigh more and more heavily on the entire rural economy. There we have the destroyer of primitive economic and social equality. It introduces heterogeneous elements, provoking in the bosom of the commune conflicts of interests and passions designed first to encroach on the communal ownership of arable lands, and then that of the forests, pastures, common lands, etc., which once converted into communal appendages of private property will fall to it in the long run.

7. Capital and landowners also threaten to devour the commune.

A certain kind of capitalism, nourished at the expense of the peasants through the agency of the State, has risen up in opposition to the commune; it is in its interest to crush the commune. It is also in the interest of the landed proprietors to set up the more or less well-off peasants as an intermediate agrarian class, and to turn the poor peasants – that is to say the majority – into simple wage-earners. This will mean cheap labour!

8. In sum:

And how would a commune be able to resist, crushed by the extortions of the State, robbed by business, exploited by the landowners, undermined from within by usury?

9. This leads to an entirely bogus ideological interpretation of the commune’s plight.

At the same time as the commune is bled dry and tortured, its land rendered barren and poor, the literary lackeys of the ‘new pillars of society’ ironically depict the wounds inflicted on it as so many symptoms of its spontaneous decrepitude.

10. However, if these political oppressions were raised, Russia’s unique opportunity for economic development would be self-evident:

Gone are the days when Russian agriculture called for nothing but land and its parcel cultivator, armed with more or less primitive tools…

But where are the tools, the manure, the agronomic methods, etc., all the means that are indispensable to collective labour, to come from? It is precisely this point which demonstrates the great superiority of the Russian ‘rural commune’ over archaic communes of the same type. Alone in Europe it has kept going on a vast, nationwide scale. It thus finds itself in historical surroundings in which its contemporaneity with capitalist production endows it with all the conditions necessary for collective labour. It is in a position to incorporate all the positive acquisitions devised by the capitalist system without passing through its Caudine Forks. The physical lie of the land in Russia invites agricultural exploitation with the aid of machines, organised on a vast scale and managed by cooperative labour. As for the costs of establishment – the intellectual and material costs – Russian society owes this much to the ‘rural commune’, at whose expense it has lived for so long and to which it must still look for its ‘element of regeneration’.

11. The commune had also successfully endured until it could be compared favourably with what Marx perceived as a failing capitalism.

Another circumstance favouring the preservation of the Russian commune (by the path of development) is the fact that it is not only contemporaneous with capitalist production but has outlasted the era when this social system still appeared to be intact; that it now finds it, on the contrary, in Western Europe as well as in the United States, engaged in battle both with science, with the popular masses, and with the very productive forces which it engenders.

12.The Russian commune is both largely immune to many familiar forms of interference and continues to practice promising forms of economic activity.

And the historical situation of the Russian ‘rural commune’ is unparalleled! Alone in Europe, it has kept going not merely as scattered debris such as the rare and curious miniatures in a state of the archaic type which one could still come across until quite recently in the West, but as the virtually predominant form of popular life covering an immense empire.

Russia is the sole European country where the ‘agricultural commune’ has kept going on a nationwide scale up to the present day. It is not the prey of a foreign conqueror, as the East Indies, and neither does it lead a life cut off from the modern world. On the one hand, the common ownership of land allows it to transform individualist farming in parcels directly and gradually into collective farming, and the Russian peasants are already practising it in the undivided grasslands; the physical lie of the land invites mechanical cultivation on a large scale; the peasant's familiarity with the contract of artel facilitates the transition from parcel labour to cooperative labour.

13. At this stage of historical social development, the option of the communal (e.g., collective property) maintaining its precedence over the individual (i.e., private property) remains open, so a direct transition to socialism appears realistic.

Either the element of private property which it implies will gain the upper hand over the collective element, or the latter will gain the upper hand over the former. Both these solutions are a priori possible, but for either one to prevail over the other it is obvious that quite different historical surroundings are needed.

The best proof that this development of the ‘rural commune’ is in keeping with the historical trend of our age is the fatal crisis which capitalist production has undergone in the European and American countries where it has reached its highest peak, a crisis that will end in its destruction, in the return of modern society to a higher form of the most archaic type – collective production and appropriation.

14. So the temporal conjunction of capitalist development and peasant commune could not be more promising.

The contemporaneity of western production, which dominates the world market, allows Russia to incorporate in the commune all the positive acquisitions devised by the capitalist system without passing through its Caudine Forks.

15. This strategy is not without risks.

The English themselves attempted some such thing in the East Indies; all they managed to do was to ruin native agriculture and double the number and severity of the famines.

16. However, Russia had already assimilated a great range of capitalist systems and structures without thereby becoming essentially capitalist:

In order to utilise machines, steam engines, railways, etc., was Russia forced, like the West, to pass through a long incubation period in the engineering industry? Let them explain to me, too, how they managed to introduce in their own country, in the twinkling of an eye, the entire mechanism of exchange (banks, credit institutions, etc.), which it took the West centuries to devise?

17. The commune remains vulnerable.

But what about the anathema which affects the commune – its isolation, the lack of connexion between the life of one commune and that of the others, this localised microcosm which has hitherto prevented it from taking any historical initiative?

18. But this is not ‘an immanent characteristic of this type’ of society. So –

Today it is an obstacle which could easily be eliminated. It would simply be necessary to replace the volost, the government body, with an assembly of peasants elected by the communes themselves, serving as the economic and administrative organ for their interests.

19. All in all, the commune’s potential is clear:

Theoretically speaking, then, the Russian ‘rural commune’ can preserve itself by developing its basis, the common ownership of land, and by eliminating the principle of private property which it also implies; it can become a direct point of departure for the economic system towards which modern society tends; it can turn over a new leaf without beginning by committing suicide; it can gain possession of the fruits with which capitalist production has enriched mankind, without passing through the capitalist regime, a regime which, considered solely from the point of view of its possible duration hardly counts in the life of society.

20. All the commune needs is the revolutionary knell:

If revolution comes at the opportune moment, if it concentrates all its forces so as to allow the rural commune full scope, the latter will soon develop as an element of regeneration in Russian society and an element of superiority over the countries enslaved by the capitalist system.

21. In sum, non-capitalist societies could adopt capitalism’s positive accomplishments to facilitate their movement towards socialist goals, without themselves being absorbed by capitalism in turn.

22. There are therefore potentially non-capitalist routes to socialism.

4. Marx’s final reply

Marx’s actual reply is dated 8 March 1881 – not yet three weeks from the day Zasulich despatched her original letter. After the elaborateness of the drafts, the final text comes as a great surprise. Apart from an opening apology for the delay in responding (!), the entire text reads as follows:

In analysing the genesis of capitalist production I say:

‘At the core of the capitalist system, therefore, lies the complete separation of the producer from the means of production... the basis of this whole development is the expropriation of the agricultural producer. To date this has not been accomplished in a radical fashion anywhere except in England... But all the other countries of Western Europe are undergoing the same process’ (Capital, French ed., p. 315).

Hence the ‘historical inevitability’ of this process is expressly limited to the countries of Western Europe. The cause of that limitation is indicated in the following passage from Chapter XXXII:

‘Private property, based on personal labour ... will be supplanted by capitalist private property, based on the exploitation of the labour of others, on wage labour’ (I.e., p. 341).

In this Western movement, therefore, what is taking place is the transformation of one form of private property into another form of private property. In the case of the Russian peasants, their communal property would, on the contrary, have to be transformed into private property.

Hence the analysis provided in Capital does not adduce reasons either for or against the viability of the rural commune, but the special study I have made of it, and the material for which I drew from original sources, has convinced me that this commune is the fulcrum of social regeneration in Russia, but in order that it may function as such, it would first be necessary to eliminate the deleterious influences which are assailing it from all sides, and then ensure for it the normal conditions of spontaneous development.[6]

Given the detail of the arguments elaborated in the drafts, this is surprisingly terse, with little reference to the ideas he had set out while preparing his answer. The irrelevance of the argument developed in Capital to non-capitalist societies is acknowledged, and the underlying problem of the forms of property is alluded to. Then Marx concludes with a very general statement as to the need to defend the peasant commune if it is to support the transition of Russia to socialism without passing through capitalism.

What is missing? The problem of the forms of property is not explained, nor are any possibilities or prognosis offered – which is to say, what Zasulich asked for. The discussions of historical forms of communal property and the unusual historical position of the Russian commune are both omitted. The argument regarding the transfer of the achievements of capitalism to other, non-capitalist contexts has disappeared in its entirety. Most telling of all, there is no reference to either the forces and relations of production that currently sustain the Russian peasants’ way of life or the changes or initiatives that might turn them into a new path, from which one might have expected Marx to have begun. In fact it is as though the drafts had never been written.

5. What does it all mean?

Looking back at Marx’s drafts, it is striking how abruptly they halt. This is not like the famous ‘Here the manuscript breaks off…’ at the end of Capital. Here we are witnessing not the cutting short of what we have every reason to expect would have been an illuminating and, politically speaking, vital analysis of class. On the contrary, as the final draft before writing his reply, one would expect a more complete, more consolidated and better articulated version of the arguments laid out in the previous drafts, with perhaps some amendments and extensions. We would also expect a more or less explicit anticipation of the final letter. But the ending of the third draft signals neither.

So what is Marx’s reason for halting quite so suddenly in this new case? Impatience? Dissatisfaction, frustration, anger? We have no reason to think that Marx lacked the inclination to address the problems raised by his correspondent or the ideas articulated in the first two drafts of his letter. On the contrary, in this period Marx’s interests seem to be very much in this direction. It seems more likely that he simply regarded at least some of the arguments set out in the drafts as wrong, and wrong enough to undermine his ability to satisfy Zasulich’s very reasonable request. Nor, apparently, did he have anything better to offer. Which particular points in the drafts he was dissatisfied with it is impossible to say, but it is noteworthy that, of the many steps of the analysis of the drafts proposed above, Marx includes in his actual reply only the first two – which is to say, the two most general – and, from Zasulich’s point of view, the least helpful.

So what began as a detailed assessment of the historical possibility of a non-capitalist road to socialism collapses into a brief, somewhat disenchanting note of comradely support. Are the sentiments suggested by this abrupt ending – in short, Marx’s inability to persuade himself of the validity of his own analysis – the reason why the final letter includes practically nothing of any novelty or use to its recipient, but instead rehearses platitudes every Marxist would be familiar with and issues unhelpful cautions against unspecified ‘deleterious influences’?

True, Marx may have some other motive for omitting the new arguments in what he finally wrote to the Russians. But there seems to be no positive reason to believe that. His express intention in writing the letter was to answer the question that the drafts explicitly deal with, but he omitted almost everything from the drafts that might have contributed to a substantive answer. His reply is polite but surely disappointed Vera Zasulich and her comrades in Geneva.

Of course, it would have suited a great many twentieth-century Marxists if he had sent something more like the drafts. A good deal of anti-capitalist revolutionism in developing countries would have been able to find a theoretical grounding in Marx’s thinking. But he did not, and his silence is as eloquent as – and perhaps more worthy of attention than – the drafts, regarding which his very silence clearly implies doubt.

Of course, the fact that Karl Marx personally did or did not say something does not make it canonical, either for Marx personally or for Marxism as a whole. Even if it is hypothesised (and it is only a hypothesis) that Marx rejected the arguments he had drawn up and had no better reply to make, it could still be that there is a general position of the kind considered in the drafts – a non-capitalist road to general societal development and to socialism – and that it is at this position that Marx would eventually have arrived, had he pressed on. Perhaps that is why he kept the drafts after sending his actual reply: he expected some such development but was not able to make it at the time. Or perhaps he agreed with enough of his own thoughts to want to retain a record of them, even if he did disagree with the principle findings. Or perhaps it was just out of habit. Rather like the drafts themselves, it is not possible to know what, ultimately, we should make of this decision. But it remains unlikely that he regarded the thoughts articulated in the drafts as ultimately convincing.

6. An alternative interpretation

From my own point of view:

As a materialist, I do not assume that modes of production cannot successfully adopt systems and structures from one another. Far from it.[7] This process can be observed everyday under capitalism itself, which has taken over everything from cookery styles to major pharmaceuticals from non-capitalist societies.

But there are limits to what can be done in this way. First and foremost, capitalism only does this in order to create new commodities. The reason for this is simple: however easily individuals may borrow from other cultures, capitalism is only able to make anything of the products of other modes of production by converting them into commodities. That is, it assimilates the creations of other social systems by reconstructing them on its own terms. A style of music that has not been converted into a commodity might appear in a personal collection, in a documentary or in a museum, or it might be adopted by a radical group as a symbol of resistance to capital. But without commodification it would be most unlikely to penetrate far into capitalist society as a whole.

This is all the more true where it is not products but new forces of production that are being adopted. Marx argues that forces developed under capitalism – ‘the machines, the steam engines, the railways, etc.’ – can be assimilated elsewhere without profound accommodations on the part of the borrowing mode of production. This seems unlikely.

For example, hunter-gatherer societies have readily assimilated many tools produced by capitalism, including not only steel knives, axes, and other direct replacements for hunter-gatherer forces of production but also more radical solutions to the problems of hunter-gatherer economic activity, such as guns.

On the other hand, as far as I am aware no hunter-gatherer society has adopted the computer or the steam engine, and it is hard to imagine how it could do so while still retaining the least shred of hunter-gatherer social organisation or culture.[8]

Nor are less obviously demanding items necessarily sustainable imports. The radio would probably be a valuable addition to the means of hunting and gathering, but it is doubtful what would happen when the batteries ran out and it became necessary to pay for new batteries with money. Not that hunter-gatherer societies have found it impossible to make occasional use of money, and trade has been a commonplace of hunter-gatherer life for tens, if not hundreds, of millennia. But the larger the volume of materials they adopted from an industrial society, the more they would need to take up a regular means of acquiring money, such as commerce or wage labour. How far this can be taken without becoming an outpost of capital is a difficult question to answer in detail but not in general – any reader familiar with the impact of money-rents and taxes on feudalism can easily guess were this tendency leads. Yet Marx appears to be arguing that, in the case of the Russian peasantry, capitalism’s forces of production could be adopted wholesale without becoming a ‘deleterious influence’.

The contrast of capitalism with hunting and gathering is of course extreme. But as its recent demolition of the Soviet system and its current devouring of Chinese Communism demonstrate, capitalism is perfectly capable of breaking down and taking over societies far more politically organised than any peasantry. The situation is likely to be much the same between any two modes of production: where there are functional incompatibilities between their respective forces and relations of production and there is substantial inequality in terms of economic and political power, it is unlikely that the weaker will long survive contact with the stronger. Since the position Marx describes for the Russian peasantry and the capitalist system from which he hypothesised so much bounty could be extracted is precisely one of a relatively weak mode of production playing supplicant to a very powerful one, it is hard to envisage the former extracting anything without paying a huge and fundamental price.

What is more, as a truly systemic mode of production, capitalism is driven to actively consume its neighbours. It literally cannot leave them alone, and it is most unlikely that the Russian commune would have the strength to keep capital out by force. One need only recall past encounters between capitalist and peasant societies to see what the consequences are likely to be.

All in all, it is not clear how, ‘thanks to’ the peasant commune’s ‘contemporaneity with capitalist production, it will be able to appropriate the latter’s positive achievements without experiencing all its frightful misfortunes’. On the contrary.

Regarding his specific claims for the Russian peasant commune, Marx provides no explanation for why a peasant economy liberated from, as he puts it, ‘the deleterious influences which are assailing it from all sides’, should undergo ‘spontaneous development’ in the direction of socialism.

In the case of capitalism his explanation for an intrinsic dynamism is of course explicit and extremely detailed, but essentially it is that capitalism forms capitals into a vast, hyperactive cyclical system that constantly replicates itself on an ever-grander, ever more comprehensive scale. This system can be confidently predicted to undergo ‘spontaneous development’ because Marx has shown how it works as a system. It is much harder to identify an equivalent dynamism in other modes of production, and in the case of the peasant commune, Marx offers no equivalent analysis.

Marx’s claim that ‘the rural commune, still established on a nationwide scale [in Russia], may gradually detach itself from its primitive features and develop directly as an element of collective production on a nationwide scale’ is also improbable.

In Marx’s day the peasant community existed as a ‘nationwide’ reality only because the thousands of communes were bound together by a largely exogenous political administration, a landed gentry and the somewhat ephemeral forces of petty commerce. Remove the aristocracy and the structures of political administration – which is to say, remove any active and explicit support for ‘the nation’ – without creating a new political system in its place and it is hard to see that a nation of any kind remains, or therefore the impetus for creating ‘collective production on a nationwide scale’.

Marx’s more specific assertion that ‘it would simply be necessary to replace the volost, the government body, with an assembly of peasants elected by the communes themselves, serving as the economic and administrative organ for their interests’ makes an interesting thought experiment, but it is difficult to envisage conditions under which this transformation could be realised.

Conversely, the idea that the peasant commune’s ‘isolation, the lack of connexion between the life of one commune and that of the others, this localised microcosm which has hitherto prevented it from taking any historical initiative… would vanish amidst a general turmoil in Russian society’ is little short of surreal. Most of what Marx himself wrote about peasant economies elsewhere would suggest that stasis or fragmentation was a more likely outcome.

As for the idea that ‘Russian society owes this much to the “rural commune”, at whose expense it has lived for so long and to which it must still look for its “element of regeneration”’, this appears to be arguing that the Russian ruling class will eventually recognise that it has been exploiting the peasantry all along, see the error of its ways, relent and make enormous recompense to the exploited. I doubt that this proposition needs any commentary at all.

That is not to say that a non-capitalist society must be instantly decimated by contact with capitalism. However, as Engels noted, this could be achieved only because the apparent agent of change, the tsarist government, was able to call upon the support of the bourgeoisie.

Another thing is certain: if Russia required after the Crimean war a grande industrie of her own, she could have it in one form only: the capitalistic form. And along with that form, she was obliged to take over all the consequences which accompany capitalistic grande industrie in all other countries.[9]

Furthermore, the adoption of grande industrie, as Engels calls it, – ‘steam, electricity, self-acting-mules, power-looms, finally machines that produce machinery’[10] – also has social and economic repercussions:

For it is one of the necessary corollaries of grande industrie, that it destroys its own home market by the very process by which it creates it. It creates it by destroying the basis of the domestic industry of the peasantry. But without domestic industry the peasantry cannot live. They are ruined, as peasants; their purchasing power is reduced to a minimum; and until they, as proletarians, have settled down into new conditions of existence, they will furnish a very poor market for the newly-arisen factories.[11]

All in all, there seems to be little reason to expect that the Russian peasantry, no matter how thoroughly liberated from the stranglehold of tsarism and aristocracy, would either have wanted or been able to develop in a markedly more collectivist direction, culminating in anything resembling a socialist society. Of course, the same arguments may not apply to other non-capitalist societies. But in the absence of specific arguments grounded in the details of the forces and relations of production underpinning the society in question, especially vis à vis those of industrial capitalism, it is difficult to imagine how a different outcome is at all likely, or perhaps even possible.

7. Conclusion

We don’t know what Vera Zasulich felt about Marx’s final letter. I doubt that either she or her comrades were very happy with it. But the effect does not seem to have been fatal: Engels and Zasulich continued to correspond for some time,[12] and in 1883, the year of Marx’s death, she and Georgi Plekhanov founded the Emancipation of Labour Group, the first Russian Marxist organisation. The question of the peasant commune – Marx’s ‘fulcrum of social regeneration in Russia’ – and the possibility of a non-capitalist road to socialism continued to be central to debates among Russian revolutionaries of all stripes.

The argument set out above should not be read as denying all hope of a non-capitalist route to socialism. All it really implies is something Marx himself mentions when he explains what actually drives the transition between any two modes of production. What is more, this is something Marx did include in his final letter to Geneva. This is the proposition that, ‘in the final analysis’, the question social revolution faces is that of transforming one form of property into another. In the case of capitalism, the formation of socialism depends on changing private property in the means of production into collective property. On that basis, what is needed is to show how any other historical process can plausibly, practically turn the form of property prevailing in whatever pre-socialist mode of production one begins with into, again, collective property. In cases like ancient slavery or feudalism there may be no such route; but there is no obvious reason to believe that capitalism is entirely unique in offering such a road.

On the other hand, a change in property is not the only condition for attaining socialism. After all, collective property is not without precedent in human history, but it is unlikely that one would want to return to any previous example. In the world of the ancient agricultural commune it seems to have been commonplace, but mimicking such a society would surely not be enough to create an advanced, post-industrial socialism. So collective property seems like a necessary aim, but by no means sufficient.

Despite the apparent hesitancy shown by his letter to Vera Zasulich, Marx never doubted the possibility of revolution in Russia or its potential contribution to the development of socialism elsewhere. A year later, in the 1882 preface to the Russia edition of the Communist Manifesto, Marx wrote:

If the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that the two complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for communist development.[13]

Evidently he believed that the potential was there. But the analysis of exactly how this would come about through the development of the forces and relations of production of a large-scale peasant society was never performed. Neither for Russia nor for any other non-capitalist society was a convincing model for the transition to socialism developed. Marx did not live to see the revolution he long predicted take place in Russia, or anywhere else. What he would have made of the revolutions of the twentieth century it is impossible to say. But it is doubtful whether his letter to Vera Zasulich would have offered the revolutionaries much in the way of guidance.

Notes

[1] An English translation of Vera Zasulich’s letter can be found at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/zasulich/zasulich.htm.

[2] For the general background to Marxism in Tsarist Russia, see Angus (2022).

[3] Outlined in Musto (2020: Ch. 2) and Anderson (2010).

[4] Marx and Engels (1975, 291-4 [Letter to the Editorial Board of the Otecestvenniye Zapisky, November 1877]).

[5] Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 24, 346-369 [Drafts of the letter to Vera Zasulich, 8 March 1881]). On the sources, see Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 24, 640 n.397).

[6] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 46, 71-2 [Letter to Vera Zasulich, 8 March 1881]).

[7] Robinson (2023).

[8] For an extended study of money’s slow but steady corrosion of hunter-gatherer society, see Wiessner and Huang (2022).

[9] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 49, 536 [Letter from Engels to Nikolai Danielson, 22 September 1892]).

[10] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 49, 535 [Letter from Engels to Nikolai Danielson, 22 September 1892]).

[11] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 49, 535 [Letter from Engels to Nikolai Danielson, 22 September 1892]).

[12] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 47, passim).

[13] Marx and Engels (2010: Vol. 24, 426 [Preface to the second Russian edition of the Manifesto of the Communist Party]).

References

For bibliographic references, click here.